|

|

|

AC Schnitzer

Adler

AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Arlen Ness

ATK

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Bakker

Barigo

Benelli

Beta

Big Bear

Big Dog

Bimota

BMS Choppers

BMW

Borile

Boss Hoss

Boxer

Brammo

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultago

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

CR&S

Daelim

Derbi

Deus

DP Customs

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley-Davidson

Harris

Hartford

HDT USA

Hesketh

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

HPN

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Italjet

Jawa

Junak

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Lehman Trikes

LIFAN

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Matt Hotch

Midual

Mission

Molot

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

Mr Martini

Münch

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

OCC

Paton

Paul Jr. Designs

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Rickman

Roehr

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Shaw Speed

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

TM Racing

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vilner

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

|

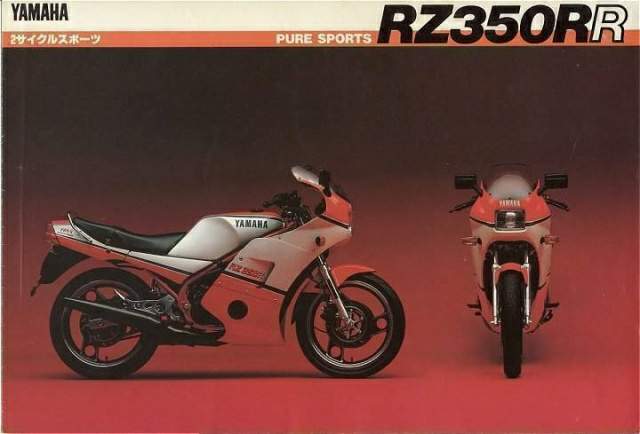

Yamaha RZ 350RR

Specification sheets display lots of useful numbers, but those numbers | don't always tell the whole story. Some-I times, a spec sheet needs yet another num-I ber, one that indicates how much fun a bike i is to ride. And on a fun scale of one to 10, * Yamaha's RZ350 rates a perfect 10. Some of those other numbers on the spec sheet, however, do help to explain why the RZ is so much fun. A look at the weight figures shows that, at 371 lb. with its 5.2-gal. gas tank half-full, the bike is light. Another number is 52. That's the claimed peak horsepower, reached at 8750 rpm. By comparison, Yamaha's 700cc Virago V-Twin, despite having a four-stroke engine twice as big as the RZ350's two-stroke, puts out only 55 claimed horsepower. So when you combine the RZ's high power with its low weight, you get another set of numbers: the quarter-mile time. The RZ350 clipped through the lights in 13.19 sec. at 99.22 mph. That's quick, especially for a 350cc motorcycle. Some other numbers aren't so impressive. Fuel mileage was 43 mpg on our official loop, but often dipped to around 30 mpg when ridden hard; so even with the big gas tank, the bike can go on reserve around 120 mi. And the stunning performance of the highly tuned engine comes at the expense of good low- and mid-range performance; so the top-gear roll-on figures are unimpressive to say the least. Numbers aside, there is something wonderfully right about the RZ350, which isn't surprising, since Yamaha has a heritage of sporting two-stroke Twins. The speedy two-strokes created Yamaha's performance image, and bikes developed from the same genetic strain as the RZ still rule lightweight roadraces around the world. And in most places around that world, Yamaha never stopped selling two-strokes for the street. Air-cooled Twins became liquid-cooled Twins, but not in America, where emissions laws and infatuation with big-bore four-strokes made the sale of two-stroke street bikes a losing proposition. So in the U.S., at least, Yamaha began losing its performance image. Yamaha, formerly the company specializing in roadracers, became more renowned for things like shaft drive, V-Twins and beginner bikes. That's all changed now. The RZ350L might be the smallest 1984 Yamaha street bike sold in the U.S. but it's no beginner's bike. Riding the RZ well requires considerable skill, largely because it comes on the pipe like no other street-licensable motorcycle. Below 6000 rpm it runs smoothly and easily, but it just doesn't make enough power to pull the skin off a bowl of rice pudding. Wait an instant more, let the tach needle slip past the 6000-rpm mark and away you go on a latter-day version of the original pocket rocket. At full throttle in first gear, the front wheel has to be held on the ground by slipping the clutch. Then it's a matter of holding on while this screaming little bumble-bee of a bike tears down the highway. You can rev the engine and speed-shift all day without worrying about a bent valve, or broken cam chain or any of that business found on four-strokes. What makes the RZ so much fun, then, is the engine. Two-stroke Twins have always been good sporting motors, but the RZ's is better than most. With a bore of 64mm and stroke of 54mm, displacement works out to 347cc. Corrected compression ratio, calculated from the point at which the exhaust port closes is listed as 6.0:1, though it's not an absolute figure on the Yamaha engine, as we shall see. A pair of 26mm slide-valve Mikuni carburetors feeds large reed valves mounted on the liquid-cooled cylinders. A small metal balance-pipe links the two intake tracts between the carburetors and the reed valves. Each carburetor also has a small rubber pipe plumbed into its front end, and that connection marks the business end of the RZ's Autolube oil-injection system. A small, crankshaft-driven pump under the righthand engine cover draws oil from the storage tank under the seat and, according to how far the throttle is opened, meters just the right amount of lubricant into the throttle bore of each carb via those little rubber hoses. That mixes the oil with the fuel so it can lubricate the vital engine internals before being burned and routed out through the RZ's exhaust system along with the spent fuel mixture. That exhaust system is critical to the Yamaha in several ways. A typical two-stroke cloud of blue smoke would be in violation of federal emissions standards, so the Yamaha is equipped with a two-stage catalytic converter in each muffler to clean up the exhaust. (Good as the converters are, they aren't enough to clean up the Yamaha to California standards, so the RZ350 isn't available at California Yamaha dealers.) To help the catalytic converters work more efficiently, there's an air-induction system in the exhaust, comprised of a small air filter, a reed valve and inlet tubes mounted just downstream of the exhaust ports, hidden by the lower engine cowling. Because catalytic converters can't erate leaded fuel, however, the gas tank has a restrictor in the filler neck so only unleaded fuel can be installed.

There also are shields around the exhaust pipes to protect the rider from the extreme heat coming off of the catalytic converters. A light and beeper connected to the exhaust warns when converter temperature reaches 1650°. But when it comes to riding the motorcycle, under all conditions, in all places, none of this emissons-related paraphernalia is apparent to the rider. The only time the RZ smokes is just after it's started. Once the crankcase gets clear of choke-richened fuel and the converters heat up to operating temperatures, the smoke goes away. Just as unusual is the rest of the exhaust. On a two-stroke engine, the height of the ports, especially the exhaust ports, determines the engine's basic state of tune. Raise the ports and the engine is tuned for more power at high rpm, at the expense of low-rpm power. Lower the tops of the ports and the opposite occurs. What Yamaha has devised for the RZ350 is the Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS), which is an electronically controlled, variable-height exhaust port in each cylinder. As engine rpm increases, a servo motor under the gas tank rotates an eccentric drum at the top of the exhaust ports thereby raising the top of the port. A pair of cables link the servo motor to the left end of the interconnected power valves. Yamaha motocrossers have used a mechanically controlled version of the YPVS, while the roadracers have used an electronically controlled version similar to the RZ's system. Variable-height exhaust port or not, there's a peculiar flat spot in the RZ's powerband. Accelerate from a low engine speed, anything below 4000 rpm, for example, and when the engine hits about 4500 rpm it just doesn't want to run. It quickly goes through this flat spot and then runs cleanly to the 9500-rpm red-line, but that one stumble can be annoying. When the RZ is in its powerband, there isn't anything annoying about it. And it was a continual amazement to us how smooth the bike is. The rubber engine-mounting system is more effective on the RZ than it is on most other bikes All the wizardry wouldn't mean much without a capable clutch and gearbox. The Yamaha is just as capable of transmitting power as producing it. Because the engine develops power so suddenly and has so little flywheel, the clutch takes terrible abuse. So far, it's survived, though the amount of freeplay at the lever varies with clutch temperature. To make use of its exciting powerband, the RZ has a close-ratio six-speed transmission. The throws are short and wonderfully light, while the gears are spaced just right for keeping the engine spinning in its happy zone. Final drive is through a 520 chain. On the RZ, as on many of the newest sport bikes, chassis design is part of the styling. A sporting motorcycle is supposed to look like a racebike, and a racebike looks like, well, like the RZ350. Notice that the gas tank looks as though it fits flat on the top frame tubes. Those top frame tubes don't fit inside the gas tank, but bend outwards from the steering head and wrap around the swing arm pivot, curving in a graceful arc under the engine to become the engine cradle. Look at the frame from the side and the top frame tubes look straight until they loop around the engine and aim back toward the steering head. This same general shape is used on the Yamaha FJ1100 and the Honda Interceptors. And on the RZ, at least, there's nothing wrong with this frame shape. It does a good job of holding all the parts in precise alignment, without being heavy or getting in the way of the rider. Nevertheless, one of the most important things the frame does is add to the race-ready appearance of the RZ. The bike may have a license plate, lights and street tires, but its overall appearance is as close to that of a racebike as any street-legal motorcycle ever made. The paint scheme, for one, is either red and white or—right off of Kenny Roberts' roadracer—yellow and black and visible a mile away. It even has Roberts' signature on the tiny fairing, just in case there's any confusion. During our time with the RZ we had occasion to park it beside a Yamaha FJ1100 and a Honda 1000 Interceptor at a local lunch spot. When we returned to the bikes the RZ was surrounded by a crowd, while the other two bikes might as well have been invisible. In fact, it became an everyday occurrence to be swarmed by curious people whenever we parked the RZ. If good looks could kill, the RZ would be the atomic bomb of motorcycles. Don't want to be looked at wherever you go? Simple. There are showrooms filled with motorcycles people don't look at. And they come cheap, too. But that brings us to price, another thing the RZ can brag about. List price is $2399, about half the cost of the big road-burners. Yes, the RZ350 is less powerful than the bikes three times as big, but it is no less thrilling to ride, since it accelerates, corners and stops better than any bike its size. A lot of new technology has found its way onto the RZ, but some currently fashionable features aren't on the bike, and aren't missed. The forks are simple 35mm telescopic units. There are no damping adjustments, no anti-dives. Air caps are fitted as the only means of adjustment. The linkage-operated, single-shock rear suspension is just as simple. No air fitting or damping knobs are installed; instead, there's only a remote preload adjustment under the righthand sidecover, with a toothed rubber belt from the remote adjuster to the shock-spring. But the suspension is simple and effective anyway. There's enough travel to keep the wheels on the pavement and the rider in the saddle, and there's no weave or wobble. The frame geometry and light weight combine to make a quick-steering bike, but one that's nc twitchy. This is a compact motorcycle too, with all the parts well tucked up. It's easy to lean way over but not easy to scrape things. Braking performance is just as admirable. Opposed-piston calipers are used on all three disc brakes. There's no annoying sponginess at the adjustable handlebar lever, just strong braking. If anything, the brakes sometimes feel stronger than normal because the engine provides virtually no braking of its own. You often come into a corner faster than you expect, clamp on the brakes and feel some kind of shock waves running through the bike as it shudders down to a slower speed. All of this, of course, fits in perfectly with the RD's purpose in life: to straighten out curvy roads in an almc effortless manner. Indeed, an RZ ride1 isn't expected to install saddlebags, tow a trailer or hook up a sidecar. There's 4^ provision for a sound system or chrometr engine guards. And many RZs are likely to log considerable time on a racetrack. They could even become the dominant club-racing bike that the old RD350 once was, a position occupied in recent years by Kawasaki's GPz550. All of this adds up to a motorcycle with an unusually narrow focus, a lightweight, repli-racer sport machine. And within that narrow scope, the RZ350 is so good, so right. You know what the bike was built to do the instant you lay eyes on it. And so does everyone else, a fact that is perhaps best exemplified by what happened the first time one of our editors took the RZ home: His three-year-old ran to the back door, saw the Yamaha and asked, "What kind of bike is that?" "A Yamaha" "Were you racing?" "No, just having fun." E3 Source Cycle World 1984 |

|

|

|